Santa Ana is about 30 miles southeast of Los Angeles and a short drive inland from Southern California’s beaches. While nearby towns are full of well-funded parks and dense foliage, only 4% of the land in Santa Ana is considered green space, and that includes a private golf course and a cemetery—both of limited use for many residents. Paving over nature until a whole city is covered in concrete doesn’t happen by accident.

On one rare patch of grass, in front of the city library, sits the bronze statue of Palestinian-American writer and human rights activist Alex Odeh—a book in one hand, a dove in the other. Many pass by without knowing the man, his work, where he came from, or his ongoing legacy.

Alex Odeh was a thoughtful family man with a wife and three daughters, described by those who knew him as a good listener and prolific writer. Born in the Christian community of Jifna, Palestine in 1944, Odeh attended universities in the West Bank until it was occupied by Israel after the Six-Day War of 1967. He fled to Egypt and then Southern California, where he taught Arabic and eventually became a U.S. citizen.

Whispers in Exile, a book he originally published in Arabic in 1983 (and which has since been out of print), was partially translated through the efforts of several volunteers in recent years. Excerpts in English reveal both prose and poetry, from a haunting memoir of Odeh’s immigration experience, to selected essays that examine racist media bias against Palestinians, and haiku-like stanzas reflecting on universal themes of love, death, truth, and dreams:

My homeland in my heart

like a flower of love,

how beautiful it is, fresh,

tender, fragrant, rejecting all the laws of aging.

On October 11, 1985, Odeh was brutally assassinated when a targeted pipe bomb exploded as he opened the door to his Santa Ana office, where he worked as the regional director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC). On that day, Odeh was scheduled to receive an award for his conflict resolution work with the local Jewish community at Congregation B’nai Tzadek synagogue.

When the Alex Odeh Memorial Statue was unveiled on the front lawn of the Santa Ana Public Library in 1994, it was considered the only full-size outdoor statue of an Arab-American person in the country (according to a Smithsonian survey). Funded by DJ Casey Kasem, whose Top 40 radio broadcasts ruled the airwaves for decades, the statue was created by Odeh’s friend, visual artist Khalil Bendib. In my phone interview with Bendib, he said the location in front of the library was chosen to represent “poetic justice.”

Actual justice is elusive. 40 years after Odeh’s murder, the FBI investigation remains unsolved, despite public outcry from the ADC, Jewish Voice for Peace, the NAACP, members of Congress, and many others. Two suspects have been living openly in contested Israeli settlements in the West Bank and one of them recently led a blockade of humanitarian aid into Gaza. A third suspect is being considered for release on parole while serving a prison sentence for another murder.

As a musician and writer who has made a home in Santa Ana, my initial curiosity about the Odeh statue led to a fascination with his writings and life story, as well as opportunities to develop friendly relationships with his family members and colleagues. On April 6, 2019, I produced an event that commemorated three milestones: it would have been Odeh’s 75th birthday—had he not been murdered at 41—and it also marked the 25th anniversary of his statue as well as the 150th anniversary of Santa Ana. With support from the Odeh family and the city’s department of arts and culture, we presented newly translated excerpts from Whispers in Exile at Makara Center for the Arts, a local community space.

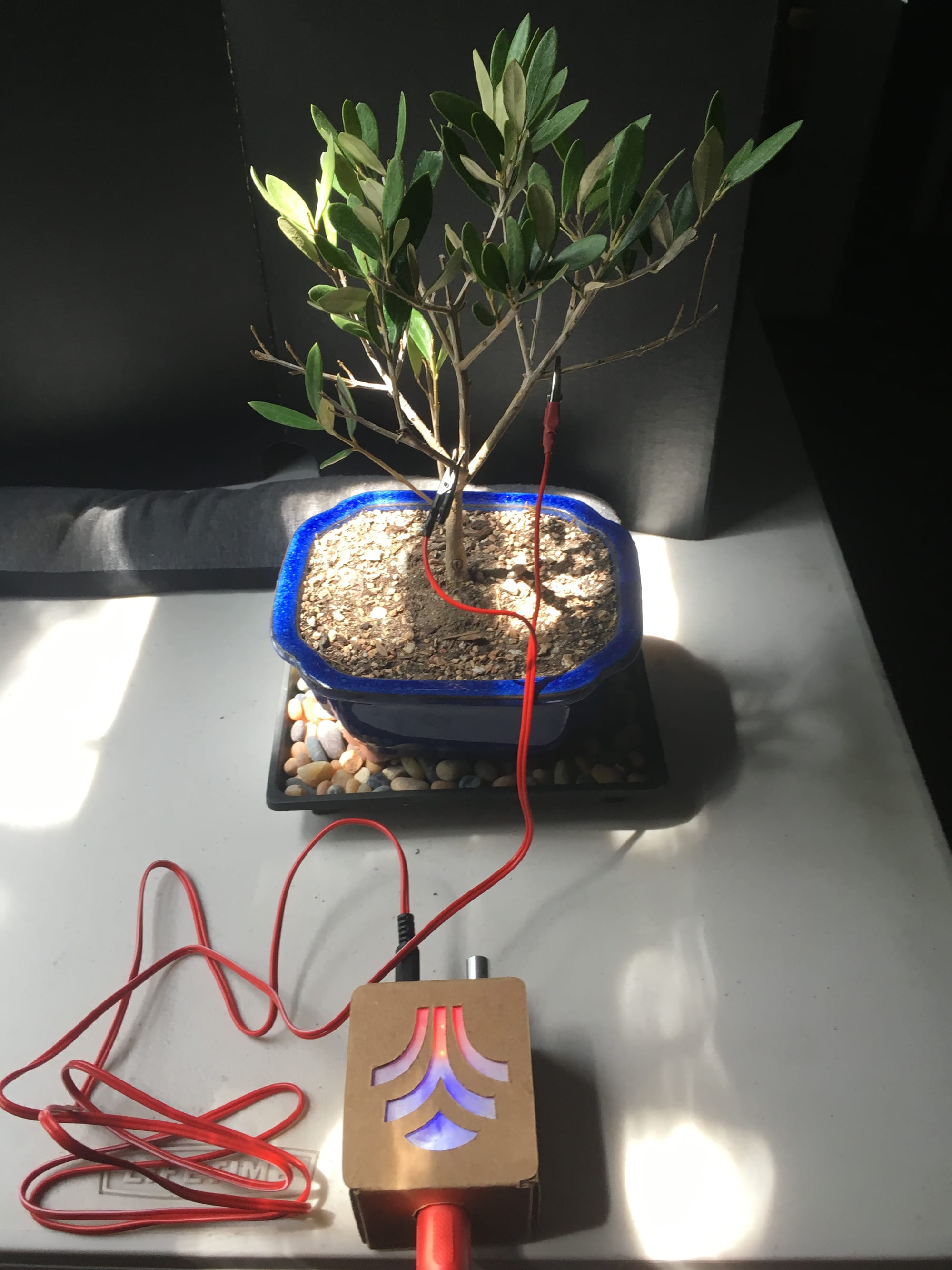

“Celebrating Alex Odeh” featured seven fellow artists and writers who read selections in Arabic, English, and Spanish—a multilingual resurrection of his words accompanied by a live soundtrack. The music was created with technology called PlantWave, which converts the natural electricity of plants into sounds. I chose an olive tree: a universal symbol of peace and a specific symbol of Palestinian resilience. For practical purposes, I acquired a bonsai-sized sapling that could be transported from studio to stage. I named my bandmate OLLIE.

This was the heaviest performance I’ve ever played. It wasn't a rock n’ roll gig at a dive bar or a hip-hop set at a club, but something far more consequential, weighted with history, and the culmination of months of research. I felt an immense responsibility to not just serve the music, but to honor the memory of a man whose life and work were significant. A fully attentive audience—including several members of the Odeh family—packed the venue, listening closely.

OLLIE was set beside me on a small green pedestal, broadcasting through speakers with myself accompanying on minimal percussion. I kept a light touch to match the ambient mood and support each reader’s delivery, signaling transitions and marking certain phrases—brushstrokes on a snare drum, fingertips on a cymbal, a barely audible hiss of a shaker filled with seeds. These sounds became grains of sand, pebbles underfoot, waves against the shore. We tumbled into the changing rhythms of travel over borders, away from home, different beats for each voice and every language.

Projections covered the wall: photos of Alex with friends, smiling at graduation, working in his office, hanging in the park. The event concluded as I led the audience in a procession outside, marching down the street to the library while playing small percussion instruments. We held a vigil on the patch of grass where Alex is immortalized in stone, observing a moment of silence while tying green ribbons on a fence, scattering prayers like leaves. Afterwards, a man wearing a keffiyeh approached me to express his appreciation for the event.

“We are not always free to even say the word Palestine,” he said.

When I gently clip the wires of PlantWave onto a plant, it’s like placing an instrument in a musician’s hands, a piece of gear that’s custom-designed for the land where they live and the stories they have to tell. Captured by delicate sensors, electrical signals produced by the olive tree were transformed into sounds created from samples of a Palestinian flute called the shibbabeh, an instrument historically made from reed, another native species from that part of the world. The result is a hybrid collaboration that connects plant, computer, and human.

My design of OLLIE’s unique sonic signature was influenced by the sensibilities of bonsai, the art of sculpting photosynthetic creatures into detailed works of art. Using the electronic effects available through Ableton Live software and the Sufi Plug-ins app, I dialed up a tuning called Bayati, which is often heard in the dabke dance styles of the Levant. The app’s digital synthesizer offers creative suggestions with pop-up text that hovers over every on-screen knob. Among the fragments of poetry are lines from 13th century mystic Rumi’s “Song of the Reed.”

Listen to the story told by the reed,

of being separated.

In essence, OLLIE played a sampler—imagine J Dilla punching pads on the MPC 3000—but in effect, they were breathing into a ghostly shibbabeh. Electronically enhanced, a mouthless and fingerless body became a virtual flutist playing an elegy from another dimension. OLLIE inserted long pauses between notes, using absence and deletion as musical techniques, leaving empty spaces for a voice that had been silenced.

While the minds of trees may be unknowable, their intelligence is indisputable. Wise elders of humans, they adapted to life on this planet millions of years before any animals appeared. Recent studies in botany are complementing the ancient indigenous knowledge that we must mutually flourish with our relatives of all species or suffer the consequences. Experiencing plants as musicians encourages a kind of enlightenment: the realization that these sensory beings who provide us with oxygen, food, and medicine have their own messages to share.

Plants operate on a long time scale, with an expansive sense of space. Life in the vegetable kingdom appears to be slow and still to us, but time-lapse photography reveals how active it can be. Plants are not single individuals, they are multiple beings with fluid identities, continuously composting death and turning life over with every sprout. Growing from the middle in both directions, bridging dirt and sky, dark and light—the roots go deep and the branches reach far.

We now find ourselves entangled together in ecological emergencies, as plant species go endangered or gone forever at an alarming rate. A simultaneous genocide/ecocide is taking place before our eyes. The destruction of Palestine is the destruction of the Earth, caused by the single-minded fascist demand of obedience to one leader, one party, one nation, one ideology.

Solutions therefore require multiplicities. Biodiversity and polyculture are equally healthy for crops, arts, and democracies. Creative actions can propagate into endless forms of solidarity—international, intertemporal, and interspecies. Trees become musicians. Sculptures transform into ritual objects. Poems written in one language become lyrics sung in another.

In prophetic words from Whispers in Exile, Odeh wrote:

Lies are like still ashes.

When the wind of truth blows,

The lies are dispersed like dust and disappear.

At least we all owe thanks to the one who tries to speak, write or paint

An honest thought to the world.