The ceiling of the Centro Ismaili’s meeting room features stars made up of tessellating hexagons and triangles, emblematic of the Islamic influence on Portuguese architecture. Four phalanxes of seats surround a stage. Orange neon tubes delineate diagonal paths between them. The opening night of Lisbon-based music festival Vale Perdido takes place here, in a gathering place for the Ismaili Muslim community. The house lights dim, and a skeletal beat plays from four speakers facing the audience.

Tristany Mundu, an Angolan-Portuguese musician and multidisciplinary artist, enters the auditorium holding a trumpet. Rather than take to the stage though, he circumnavigates it. Behind sunglasses, he fixes the front row with an interrogative gaze. Finally, he picks up one of the neon tubes lining the paths and triggers a set of automated curtains to open. They reveal a wall made entirely of glass panels, through which we can see one of the Ismaili Centre’s immaculate patios and a microphone stand.

Inexplicably, Tristany exits through one of the doors and over the next ten minutes or so sings and plays the trumpet from outside, wordlessly and mournfully. At one point, he climbs up part of the concrete lattice exterior of the auditorium, his microphone picking up knocks and clangs that fuse with the sparse music still leaking from the four speakers.

Because of how the chairs are arranged, only a quarter of the audience directly faces this unusual performance, while half must crane their necks to see. I sit with the last quarter of the audience who must either turn around completely or accept that the experience will be auditory only. The audience members in my section don’t agree on what to do. Some swivel awkwardly in their seats. One woman, after some time, stands up to turn her chair around. Others sit still in meditation, eyes open or closed. Some chat amongst themselves as if still waiting for the performance to begin in earnest. I find myself torn between contorting myself to witness this strange tableau and protesting the fact that our comfort doesn’t seem to matter.

Finally, Tristany re-enters the room, gives the audience the middle finger, and passes the neon tube to an audience member with a gesture that indicates she should hold it righteously above her head as he departs.

She does not.

He leaves.

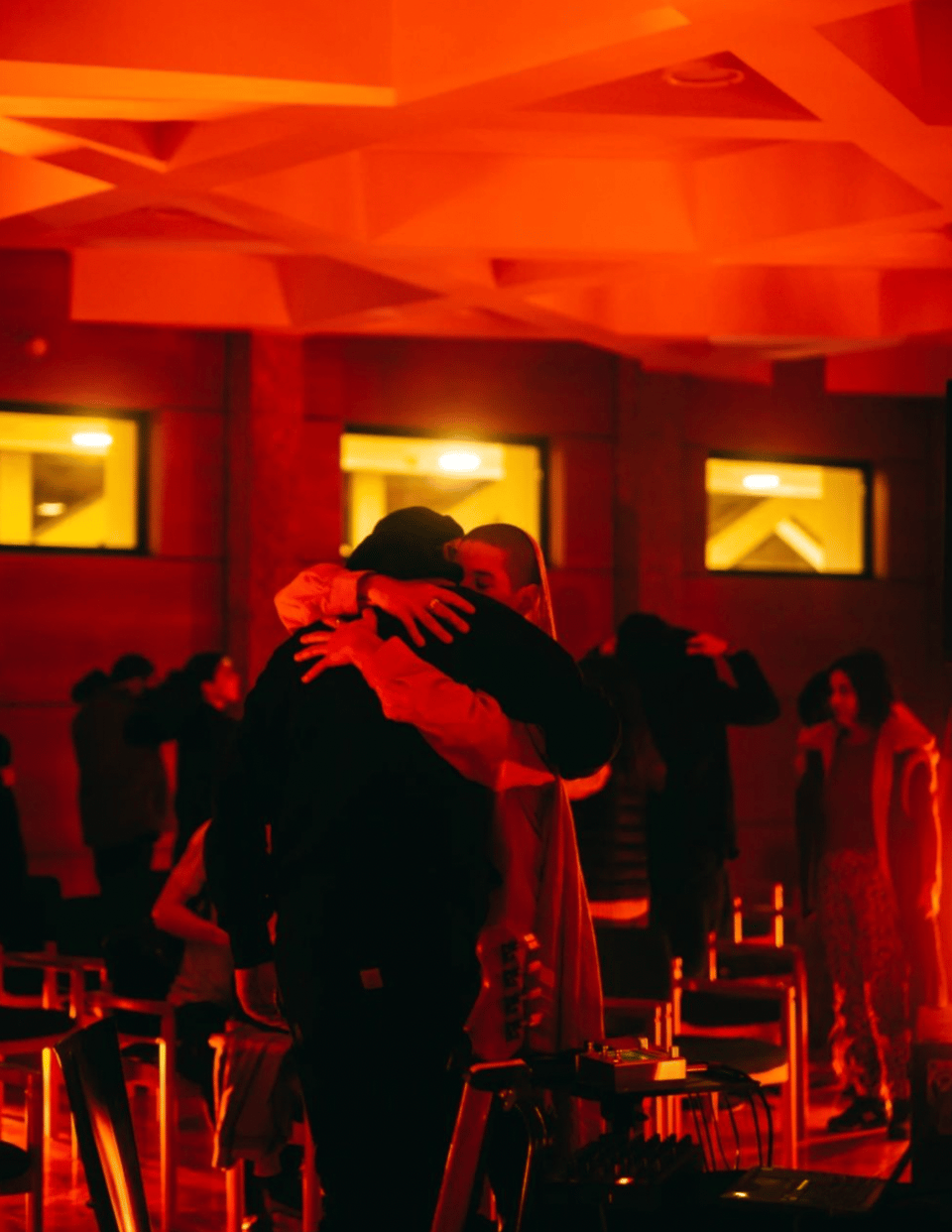

Tristany Mundu, @veramarmelo

With Tristany’s peremptory exit still lingering in the air, Palestinian musician Dirar Kalash and Algerian vocalist and somatic practitioner ãssia ghendir take to the stage. Dirar resembles a beatnik in a black hoodie, beanie, and spectacles. ãssia conjures a kind of punk nun in leather trousers, an untucked school uniform, and a head covering. ãssia paces around the stage carrying an incense burner, smiling briefly at us before settling on a solitary chair. Dirar lays his bass guitar flat on his lap. He seems to melt into the task before him as his hands delicately coax echoes out of his instrument, which are then fed through an effects box that sputters with static every time he touches it.

ãssia contributes a sharp breath that hisses, keens, then slowly flourishes into full vocalisations, wordless like Tristany’s song, rising and falling in waves over Dirar’s improvisations. ãssia’s face is a miracle to observe as they sing, seized sequentially by different emotions. From grief to rage to astonishment, they lapse occasionally into what I perceive to be an almost parodic tragicomic mask. The moment I acknowledge this possibility, my brain is flooded with questions about my relation to art from cultures outside my own white, western bubble.

Am I unable to take this art at face value? I notice the layer of cynicism, then sensitivity, then shame that sits suffocatingly over my capacity to see and hear the person before me. It’s impossible to know if there is a satirical element to ãssia’s performance, but the thought contaminates my reaction to Dirar, whose demeanour and improvisations for stretches really do seem like affectations designed to appease Lisbon art scene sensibilities. At times, his performance appears to be saying: These motions must be gone through. The vultures must have their culture before the real message can be received.

But then I think: Why shouldn’t Palestinians also indulge in obtuse improvisation, like anyone, like us? Why shouldn’t Palestinians also live their lives free of occupation, like anyone, like us?

This psychological step from innocuous navel-gazing in one moment to excruciatingly real political and existential realization in the next occurs again and again as ãssia’s voice crescendos. It follows me as they walk around the stage, as they circle the audience, now visible, now not, the wordless litany increasingly distorted by Dirar’s machines into feedback and static. The outside world continues to intercede. The architectural shell of the hall, especially its starry ceiling, rattles vulnerably in different places with the frequencies of Dirar’s amplified guitar.

At one point, the stage lights fry into ebullient flashing, drenching the room in disco technicolour until, in what appears to be a climax, a technician pulls the plug. Dirar’s laptop switches to screensaver, and he repeatedly tries and fails to enter his password. We feel the message disappear behind the petty bureaucracy of daily life, whose origins feel meaningless and beyond reach.

Later in the performance, ãssia kneels silently next to Dirar, who puts down his guitar and begins to trigger field recordings from his laptop. Grinding metal, children chanting, squalls of noise, possibly munitions, possibly something else. Dirar rocks back and forth in his chair for a minute or two at a time, looking toward the ground. He tweaks the sound, then he’s back down again, rocking.

Any notion of satire is long gone.

The audience is split in their reaction. Some seem rapt; others shuffle in their seats, looking around; others make a discreet exit. The lighting team makes the orange neon tubes pulse, which I find distracting at first. But then the play of the lights on the ceiling draws my attention to the hexagons and triangles, now thrown into shapeshifting relief like the rushing onset of acid visuals.

It’s in this moment that I realize how, if not outright psychedelic, this experience feels profoundly psychoanalytical: of the concept of boundaries, the insufficiency of language, the divide between self and others, symbols and layers of meaning, feelings disowned and projected, integrity and disintegration, damaged objects and the work that might be done to repair them, a glass wall, a starry ceiling, a wordless litany, a middle finger.

As the performance comes to a close, Dirar interrupts the audience’s applause to address us plainly:

“I am not a musician. I am a Palestinian.”

He explains that while the more recent sounds we heard were taken from news reports viewed on his phone, the older recordings, including the sound of live explosions, were recorded directly from when he lived in Ramallah. His intention in presenting these sonic records is to allow Palestine to live on through those who hear it, in spite of systematic efforts to erase its culture and history.

“Bombs drop there so that they do not drop here, but they might,” Dirar finishes. “We can’t stop the genocide. Palestine will be free.”

Dirar Kalash & ãssia ghendir, @veramarmelo

What was the effect of Tristany entering the room only to leave it again to perform outside? To refuse the stage and disrupt the boundaries between inside and outside, “serious” performance and spectacle, business-as-usual and something new?

Perhaps his music, his emotions were too precious for this cloistered audience of privileged scenesters, comfy in our guestlist seats. Perhaps unfairnesses so deep that words failed to do them justice — racism, police brutality, genocide — transcended the petty etiquette of a festival opening night concert. What really mattered was happening outside our rarified glass-encased spaces, behind the curtains, trying yet catastrophically failing to penetrate our moribund attention.

The lineup for this concert originally promised a collaboration between Palestinian musicians Maya Al Khaldi and Sarouna and Palestinian visual artist Dina Mimi. We were informed a few days before the concert that the trio were unable to travel to Lisbon.

The emailed statement reaffirmed that their performance remained essential to the narrative of the festival’s programme and that Dirar Kalash and ãssia ghendir would “pass on the message” with their performance.

That evening’s programme didn’t feel like a show for our entertainment, nor the opening night of a festival, but rather a reclamation of space.

It is on all of us to make sure the curtains stay open.