“How do you still wage a war of resistance from inside a prison cell? Smiling. By smiling you know and you know seeing victory. We will win.” — Hussam Shaheen ‘Zahaika’

Listen closely and you will learn that blues means more than music. If you listen closely, you will learn from blues more than music, lyrics, or poetry. The blues is a Black proletarian school of thought, one that teaches how Black people will prevail, and Langston Hughes was one of its great educators.

The Black Radical Tradition in the United States is rooted in that wisdom of the working class. Though thinkers like W.E.B. Du Bois contributed to revolutionary theory, it was the lowly laborers like the young Langston Hughes who constituted the very core of revolutionary consciousness. Political education, mass consciousness, and radical tactics are outgrowths of that intellectual seed planted by the Black proletariat. Critical geographer Clyde Woods referred to this kernel of knowledge as the Blues epistemology, “grounded in the economics of slavery” and cultivated in non-collegiate sites of education. Hughes’s 1920s “working-class ideology,” as Jonathan Scott calls it, was the blueprint for his Marxist organizing in the 1930s. While some scholars have suggested that he lost, inverted, or even rejected the perspective he used to write blues poetry, I believe Hughes’s activism is a ripened fruit of the same philosophical seed in his writing.

Placing Black radical pedagogy in the context of the blues is not purely aesthetic. It is the key to building working-class consciousness. Today, more than ever, teachers and learners are the protagonists of revolution in the United States. Hughes shows that students of history, students of material conditions, must be students of the School of the Blues.

While conducting literary analysis of Hughes’s autobiography, biography, poetry, and essays and looking for themes of education, I found two sites representing the blues epistemology. The first is the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, later known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The second site was located four miles north of Montgomery, Alabama, and held hundreds of young Black men including eight who Hughes would meet in 1932. It was called Kilby Prison. These sites could be considered an allegorical School of the Blues, where Hughes learned and taught twin principles of hope and high morale.

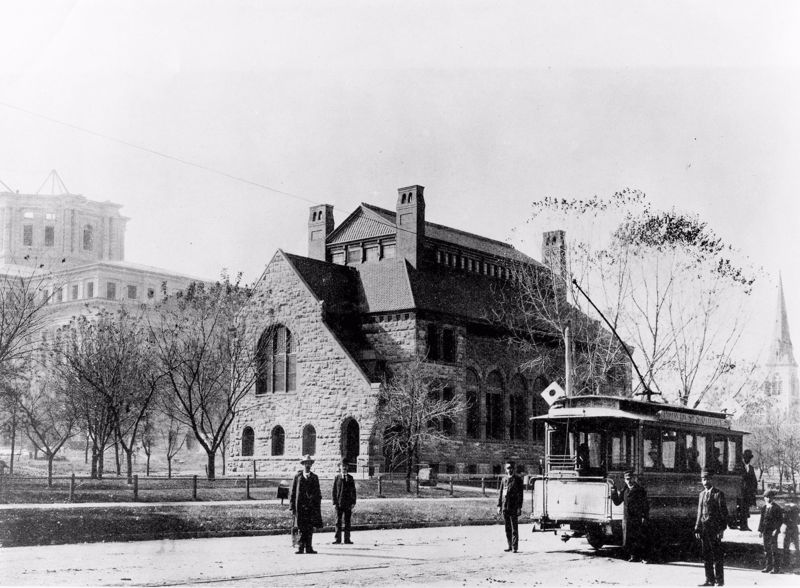

Before enrolling him in school, Langston’s mother Carrie often took him to the small public library in Topeka, Kansas. Workers there attended to his desire to read, kickstarting his lifelong Camaraderie with librarians like Arna Bontemps and Regina Anderson. This was not a privilege shared by many young Negros at the turn of the century. Public libraries were not established in Black areas and most would not integrate for decades, but “books began to happen” to Lang in Kansas in 1905. That same year, 1,300 miles away, the New York Public Library opened a branch in the Jewish and Italian neighborhood of Harlem. During the Great Migration, the neighborhood began to welcome Negros en masse. New arrivals in Harlem reoriented the library's focus from a white patronage to a diverse Black population, just as Black people had repurposed Western instruments to create blues.

The New York Public Library developed an expansive “Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints” at a time when colleges were uninterested in Black studies. When– according to W.E.B. Du Bois– a Black man could “complete his education without any idea of the part which the black race has played in America.” It boasted texts, art, pamphlets, and engravings, as concrete evidence against the notion that Black people were without their own history. In my forthcoming 2024 journal article, I argue that lectures and debates by socialists and Communists at the site fit perfectly into Harlem’s sonic landscape. In “Development Arrested,” Clyde Woods argues that, “The essential motive behind the best blues song is the acquisition of insight [and] wisdom” from the spirit-raising stories, songs, and jokes of laborers. Whether “porter, professor, nursemaid, student,” as Head librarian Ernestine Rose says, the ordinary people frequenting the Harlem Branch reflected the protagonists of the blues. According to her, “The application desk of a public library serves as a doorway into the ‘other half' of many lives, the half which lives while not working for a living, the half which thinks, aspires and endures.” This accessible knowledge brought light and levity to the allegedly dark past of Africans in America.

Hughes sought out the library on his very first day living in Harlem in 1921. It was his second destination after the local YMCA, where he was staying. The 19-year-old would soon make the library his go-to locations for work, hangouts, and even dates. The site was a laboratory for him to safely experiment with new stylistic forms. Take for example the time he submitted his “syllabic poem” to one of the library’s poetry readings. Hughes asked Countee Cullen, the prim young man for whom the library branch is named today, to read on his behalf and announce that “it is poetry of sound, and it marks the beginning of a new era, an era of revolt against the trite and outworn language of the understandable.”

Ay ya!

Ay ya!

Ky ya na mina,

Ky ya na mina.

You can imagine the rigidity with which Cullen delivered this poem, considering that he was unsure if even Hughes’s developed blues was truly poetry, and that even in jazz, scatting would not appear until 1926. This new presentation of Black art, oration, and history brought hope for a radically different future, and allowed folks to voice what it would sound like.

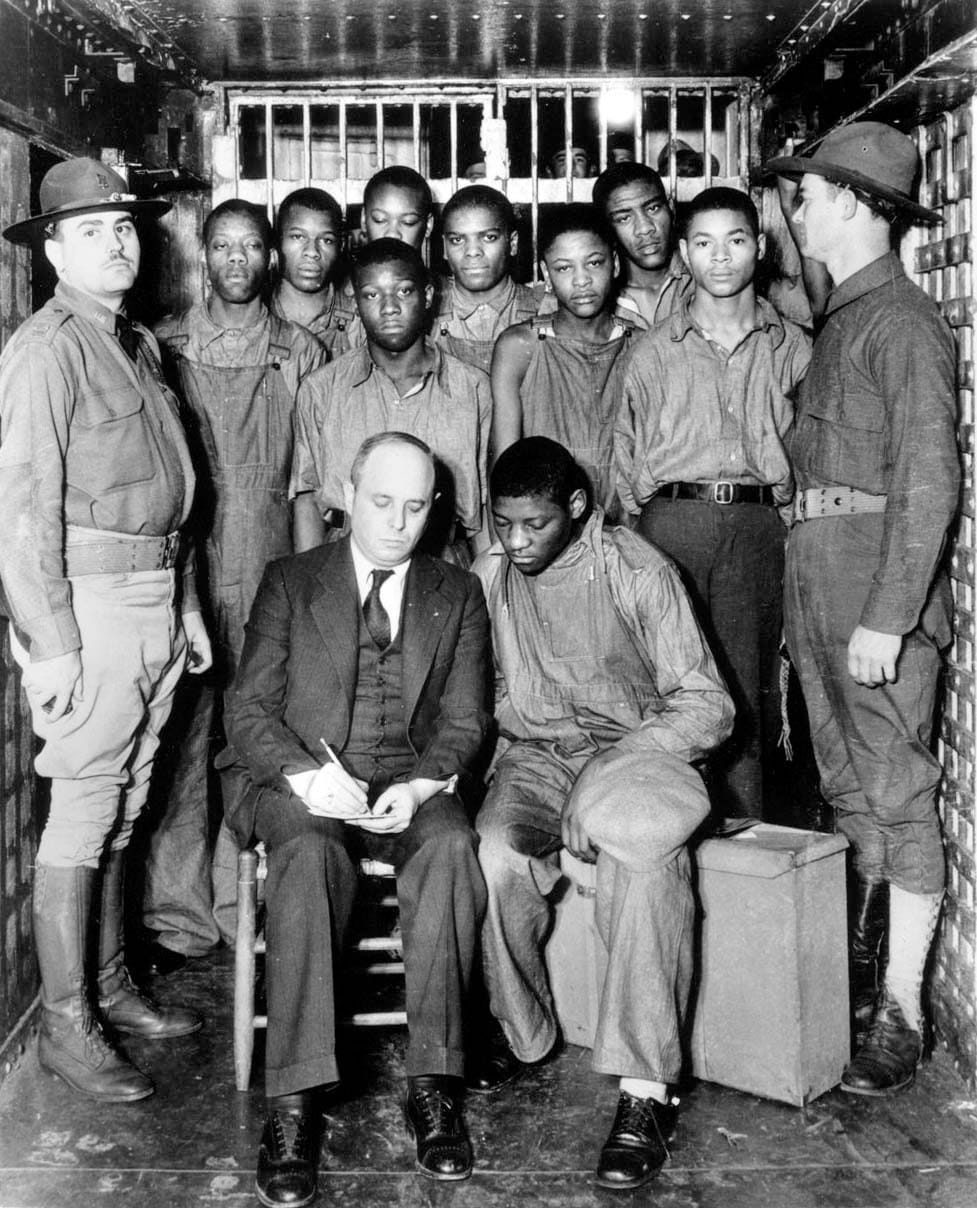

A decade later, in 1932, Hughes facilitated an informal class in Kilby Prison. In attendance were Ozie Powell, Charlie Weems, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams, Roy Wright, and his brother Andy Wright– known as the Scottsboro Boys. Held captive at Kilby Prison and aged 14 to 21, they were placed on death row after being falsely accused of raping two white women. Arnold Rampersad describes Hughes entry into the allegorical classroom: “Steel gates opened and clashed, opened and clashed behind him until he reached a two-story building deep within the compound. On the second floor were the death cells. One room held sixteen cages, all occupied by blacks. Beyond the hallway, behind a green door, was the electric chair.”

This wasn’t Hughes’s first visit to Kilby. In fact, he dedicated himself to the case after meeting the Scottsboro Boys in 1931. The case became a rallying cry for the Communist Party (CP) from which Hughes’s friends Louise Thompson and William Patterson championed the fight. Though Hughes never officially joined the party, his alignment with it can be explained by advice he received in 1927 from George Schuyler, the secretary of the adult education committee at the Schomburg: “What the black masses need […] is hope and pride, an understanding of their potentialities, a reinforcement of dignity. I believe you can be of great service to this end because you have the proletarian point of view.”

“Scottsboro Limited,” his “Marxist one-act play” published in the New Masses and staged from Los Angeles to Moscow, represented his expressive approach to the political crisis. He became involved with the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, a CP-adjacent organization of which he would later become president. Just as many blues singers performed abroad in the 1930s, Hughes delivered his most attended speech of that decade while in the Soviet Union, where American Blacks had earned “instant prestige” for their steadfastness. While jazz was taboo in the USSR, Hughes’s focus on these working-class Black youth anchored his speech in the blues. According to Jonathan Scott, “The successful recruitment of Langston Hughes into the ranks of the CPUSA’s Scottsboro Defense Organization [was] arguably one of the party’s greatest victories on the cultural front.”

Whereas jazz music was illegal in select schools throughout the U.S.– and songs like “Jailhouse Blues” were considered taboo– Hughes’s blues-coded lectures taught many about the trial. They emphasized perseverance of the Black masses despite catastrophe. He was an exception among educators, however. During a lecture tour, he realized it was taboo to even mention the Scottsboro boys at many Black colleges. In a 1934 article in The Crisis, titled “Cowards from the Colleges,” he criticized educators, writing, “with demonstrations in every capital in the civilized world for the freedom of the Scottsboro boys, so far as I know not one Alabama Negro school until now has held even a protest meeting.”

When Hughes again visited Kilby prison, during his lecture tour of the South in 1932, the boys were not interested in Hughes’s poetry nor in his description of the mass movement to free them. After all, what could an urban poet teach them? They knew they had the blues. Deathrow provided a unique perspective on what Bessie Smith described in “Downhearted blues,”

Trouble, trouble, I've had it all my days

Trouble, trouble, I've had it all my days

It seems that trouble's going to follow me to my grave

However, Hughes imparted to the boys the very hope and endurance which he learned from the 135th Street Library. He reminded them that working-class people were fighting incessantly on their behalf, specifically Ada Wright, mother of Roy and Andy, who quit her job to defend their case. The sober persistence of the blues is evident in a letter which she concluded by saying, “whatever happens I can see clear now, and whether my boys live or die I'm in the fight as long as I live.”

As Arnold Rampersad recounts in his book “The Life of Langston Hughes,” the boys neither rose from their bunks nor greeted the poet when he approached. He felt somewhat defeated as they were literally unmoved by anything he had to say, read, or reflect on. However, when Hughes mentioned hearing Mrs. Wright speak at International Labor Defense rallies, Andy stood, smiled, and shook the poet's hand through the steel bars. This concluded the lesson.

In the spirit of the Harlem library, Hughes convinced Andy Wright that ordinary people were leading the fight to save them. He raised morale in a seemingly hopeless situation by demonstrating that working-class people could start a worldwide movement. The lesson did not eliminate the dread of a possible death penalty nor of years in prison. It did, however, help Wright persist amid catastrophe.

2025 marks the centennial of the Schomburg center, a site which has introduced many to the Black Radical Tradition. Despite Mayor Eric Adams’s attempts to defund the system, the New York Public Library remains a major arena for popular organizing. Students of history, who apply Marxist frameworks outside of the classroom, meet at the library to challenge American imperialism, austerity, and intellectual complacency by speaking out and studying in. In the scathing and patient spirit of the blues, Langston Hughes continues to provide critique of those who refuse to teach the lessons of revolution, and hope for those studying how to struggle amid scholasticide. Those who are punished and arrested for continuing his legacy, who are fired, expelled, and harassed for learning from working class Black revolutionaries, are students of the School of the Blues.