In a time marked by political alienation, racialized violence, economic uncertainty, and emotional burnout, collective joy may seem frivolous. What if though, that joy could be more than an escape— but an act of resistance driven by human need? What if dancing together, to music rooted in struggle and transcendence, becomes a method of healing that is both personal and political? In many marginalized communities, dance spaces— especially those shaped by Black, queer, and migrant histories— have long served as informal therapeutic environments. There exists something deeper: an intersection of music, neurobiology and trauma recovery, where intentional community design can transform a dance floor into a site of radical repair.

Neurobiology of Music and Trauma

Music doesn’t just sound good; it does something to us. Neuroscientific studies have long shown that music stimulates areas of the brain involved in memory, emotion, and motor coordination. Particularly, rhythmic music activates the basal ganglia and motor cortex (critical for timing, movement, and repetitive motor actions), while emotionally resonant sounds trigger the limbic system (integral to processing emotion and memory)(Thoma et al., 2013). Mirror neurons (brain cells that respond to the actions of others) light up when we see someone dancing or feel the tension of a DJ building a breakdown. These mirror neurons allow us to emotionally and physically sync with those around us.

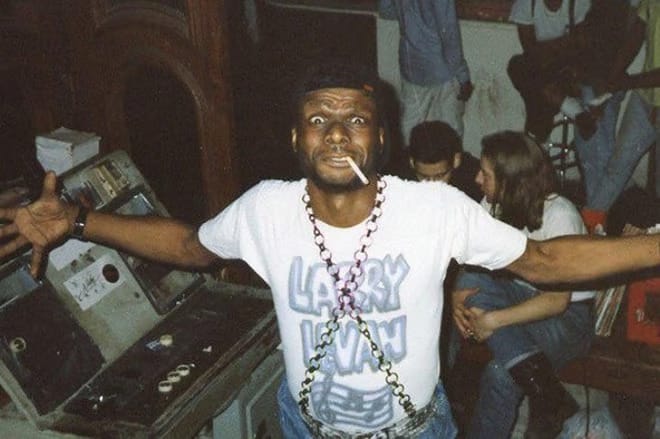

During moments of collective suffering, such as the AIDS crisis, these connections took on profound meaning. At the Paradise Garage in New York City, under the visionary direction of DJ Larry Levan, gay men— especially Black and Latinx men— found a space where rhythmic breakdowns in house and disco offered emotional release and communal healing (Lawrence, 2016). Levan’s sets often fostered a communal vibe that encouraged close dancing. In partnered or group forms, this creates shared rhythmic entrainment, the synchronization of movement and rhythm between bodies. While direct scientific studies on partnered dances like the Hustle at Paradise Garage are scarce, the principles of entrainment and co-regulation, key neurobiological mechanisms, are well documented (Josef et al., 2021). It’s possible Levan, by centering community and connection, was ahead of his time in cultivating a space where music and movement helped reprocess trauma through physical motion.

Amid the stigmatization of GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), this music became a sanctuary of survival rather than mere escapism. Community newsletters from GMHC (Gay Men's Health Crisis) documented how dancing lowered panic attacks and facilitated somatic awareness (GMHC, n.d.). Yet, often overlooked are the harsh realities that made these moments among the few outlets for gay men, especially when politics criminalized their very existence.

Escapism or Embodied Resistance?

Too often, dance is framed as escapism. But for those navigating trauma, escape can be regulation: a way to reclaim control, presence, and, perhaps most powerfully, a return to one’s agency. From a psychological lens, especially in trauma recovery, co-regulation is vital (the process by which our nervous systems calibrate through proximity to others)(van der Kolk, 2014). Dancing in community creates a shared rhythm that helps rewire our nervous systems.

This tradition traces back to the earliest house and techno movements in Chicago and Detroit — Black and queer communities who transformed rhythm into a language of resistance and renewal (Brown, 2022).

Having dedicated my studies to trauma and resilience, and my adult life to organizing and working within club spaces, I’ve witnessed this phenomenon repeatedly. At events where the music is curated with emotional pacing and the space is shaped with collective care, something shifts. Strangers begin to breathe in sync. People cry on the dance floor—not in sorrow, but in relief. Nights unfold as much more than music. They become acts of repair, resistance, and resilience. This is not abstract idealism. It’s neurobiological and embodied. When people feel safe in a space, their amygdala (the brain’s fear center) relaxes. When the beat drops and the body releases tension, cortisol levels fall. When we laugh and sing with others, oxytocin (the bonding hormone) rises. Our actions in these spaces and how we connect with them have a real, measurable basis in how our brains and bodies function.

The healing and resistance you see on the dance floor aren’t just poetic notions, it’s deeply rooted in our biology and psyche. Our brain chemistry shifts, our nervous system finds balance, and our bodies move in ways that soothe trauma. Some might call it abstract thinking, but it’s not. It’s the lived, felt reality of connection, and it’s clear that collective joy is not a luxury or an escape. It’s a vital part of how we survive and reclaim our wholeness.

Creating spaces with intention

Dance floors are not inherently radical. They become radical through intention. The politics of a party— who organizes it, who it centers, and how it welcomes others— play a central role. This is the philosophy behind some platforms and collectives: community-rooted events that strive to build spaces where marginalized people feel seen, safe, and free, not only to dance but to exhale.

Intentional raving is possible, and it means interrogating everything at the concept stage: is the event accessible? Is the door policy transparent? Do we offer harm-reduction tools, quiet areas, or cultural programming that both educates participants and fosters liberation? These small design decisions shift the dance floor from a site of consumption to one of co-creation and healing. The goal is to eliminate the transactional feeling of “party-as-product” and restore collective ownership of the night by centering those on the dance floor.

From the Personal to the Political

Today, as crises proliferate— from the genocide in Palestine to the rise of authoritarian governments— many organizers are returning to the roots of nightlife, in which spaces are utilized to love, to rage, and to dream alternative futures. Where politics live beneath the surface, and gatherings are designed with intention. Fundraisers, teach-ins, and cultural interventions are being held in clubs, reminding us that joy and justice can co-exist. When the dance floor is aligned with ethical practice, it becomes a microcosm of the world we want to build.

Every breakdown in a track must resolve. After the night ends, what’s left? The political potential of the rave lives in what we do with the energy it generates. Do we use it to regenerate and empower the most vulnerable, build coalitions, support mutual aid, and challenge oppressive structures around us? Or does the moment fade like a dopamine hit?

Dance as a Form of Knowing

To dance together is to remember what our bodies knew before language. It is to say: I am here, with you, and we are alive. In the darkest moments, when politics fail and grief overwhelms, dance remains. Not as denial, but as defiance. As care. As kinship.

The healing power of dance lies not just in its rhythm, but in its recognition. Through synchronized movement, we activate neural circuits tied to empathy, trust, and co-regulation. We mirror each other not only physically, but emotionally. Our brains respond to shared rhythm with a release of oxytocin, dopamine, and endorphins, all organic processes that soothe the nervous system and remind us we’re not alone (Hutchinson & Moloney, 2023).

When we examine recent psychological neuroscience, we find that intranasal oxytocin increases movement synchrony during dance, reinforcing kinesthetic empathy among participants, particularly those with higher trait empathy. These findings suggest that when bodies move in unison, our brains align too: the limbic system down regulates fear responses, while reward and bonding pathways become activated. Even clinical studies with older adults show seated dance can generate intra- and inter-brain synchrony, improving emotional and cognitive integration.

In essence, these are scientifically grounded experiences showing how dance fundamentally reconfigures our brain chemistry and neural architecture in real time. Collective joy when gathered with intention, then, is not indulgence, rather it is neurobiological resistance. It reminds us that together, in rhythm, we remember ourselves and each other. And sometimes, that is enough to begin again.

Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). (n.d.). Community archives and reflections. GMHC. [Link]

Hutchinson, M., & Moloney, G. (2023). More than just movement: Exploring embodied group synchrony during seated dance for older adults living in residential aged care communities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 43(6). [Link]

Josef, L., Goldstein, P., Mayseless, N., Ayalon, L., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2021). The oxytocinergic system mediates synchronized interpersonal movement during dance. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 13306. [Link]

Lawrence, T. (2016). Life and death on the New York dance floor, 1980–1983. Duke University Press. [Link]

Thoma, M. V., Ryf, S., Mohiyeddini, C., Ehlert, U., & Nater, U. M. (2013). The effect of music on the human stress response. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e70156. [Link]

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books. [Link]